Bio

O SAY CAN YOU SEE?

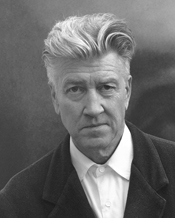

While I was making plans for other things, film and media studies found me. And in the spirit of the creative process of my future hero, David Lynch, once it entered my mind, it called to me, growing incrementally until it showed me what part it was to play in my professional life.

I was on a different academic path, teaching English and American literature, when my then very young, but already intellectually adventurous, son, David, found Tania Modleski's book The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory at a book stall near the Plaza Hotel, abutting Central Park in New York City. He gave it to me for my birthday.

Was I a woman who knew too much or not enough by miles and miles?

I ran breathlessly around the Freudian twists and turns Modleski careened on as she explicated Hitchcock's great films: Rebecca, Suspicion, Vertigo, and my favorite, Notorious. I examined her every feminist footnote, and ran those sources to earth in all the libraries open to me. The questions Modleski posed about how sexual identity was constructed in Hitchcock's movies and her forays into the patriarchal unconscious blasted away old, tired platitudes about Hitch's misogyny. I found myself longing for and finding more mind-energizing critical experiences about any and all movies, until suddenly--voila--I too was in possession of theoretical language and ideas, exploding old prejudices. And finding out just how dangerous such an undertaking could be. For every reader who was delighted by my first critical foray into provocation, there were five angrily opposing my impudence--and some of them were the very critics who had inspired me with their refusal to nod dutifully at cliches. Some scholars and critics here in the United States and some half a world away were enthusiastic. Closer to home, my daughter Holly and my husband Richard had their doubts. They (supportively) reminded me that my turf is the road less traveled.

Not everyone who had issues with my work was supportive.

Trail-blazing feminists had taught me to look closely at the way Hollywood does allow self-defining, assertive women onto the screen, but then clips their wings at closure; and I followed that train of thought into daytime television, where there is no closure. My explorations were fueled by the opportunity to write and edit for five network soap operas–Ryan's Hope; Search For Tomorrow; Guiding Light; Loving; and Santa Barbara. Through practical and theoretical means, I pondered whether the lack of closure in soap opera stories meant that women were not deprived of their possibilities in THAT medium. In No End to Her: Soap Opera and the Female Subject (1993), I argued that to a great extent that was exactly what the virtually endless story did mean, and that it COULD mean the same for other categories of characters that were also oppressed by what happens at the ends of Hollywood movies: minorities and gay characters. It COULD also generate a valid aesthetics of visual storytelling, different from those of stories that come to closure.

A positive reading of soap opera? Some colleagues were horrified. Fortunately, I made my first voyage into publishing under the tender care of my first editor, Ernest Callenbach, now retired, then of the University of California Press. After the Press gave me a contract, he told me I could call him "Chick." Of course, it was merely a nice little flourish. But it meant so much to me. I was not only validated as a scholar, I was part of the circle. His courage in backing my book allowed me to begin speaking in a (controversial) public voice. I am still pondering how the (virtually) endless narrative of soap opera works, and especially how its potential for liberating stock characters has been affected (negatively) by social developments in our country in the last 18 years since No End To her was published.

And my teaching?

Of course, it took a turn, eventually leading to my position teaching at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, my development of a Film Studies Major at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York, and my discovery of the Film Studies seminar, part of the University Seminars system at Columbia University, now an important force in my professional life. The seminar is a crossroads where many accomplished and invigorating film and media studies scholars move in and out of my path, a feast for the questioning mind, a party for the questing soul.

Then David Lynch's Blue Velvet found me

It took my breath away. I was still busy with my soap opera adventures, but, dazzled by the film, I incubated the embryonic questions it begat in my brain until Twin Peaks appeared on ABC-TV and I suddenly knew that I had to write about Lynch. Through a combination of persistence and miracles, I found myself at his door and began a five-year process of interviewing him that resulted in The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in Hollywood (1997), and what looks to be my lifelong passion for his work. There will be a second book in due course, covering his work after 1997. Again, I was indebted to a great-hearted, imaginative editor. This editor, Jim Burr, of the University of Texas Press, has remained my friend, and I continue to work with him. Lynch and I have remained in contact, and in 2012 when he came to the New York Film Festival to show Inland Empire, we took time out to laugh about how long we've been talking.

Lynch's unique and visionary use of the popular media changed my vision

What I learned from talking to him and from discussing his films in detail has inspired me to investigate unsuspected energy and innovation in sometimes surprising places in Hollywood movies and American television. These journeys have led me to question indiscriminate scholarly contempt for the phenomenon of the couple in American and international entertainment and to excavate the much misunderstood phenomenon of the screen gangster, in, respectively,

My fascination with the screen gangster led me to Silver Cup Studios in Long Island City, New York, and the office of the creator of The Sopranos, David Chase.

A fellow Lynch enthusiast, Chase was, long before I met him, the catalyst for my book on gangster films. It was his television series that re-opened the gangster film case for me, impelling me to look with fresh eyes at where the genre had been before he built his revolutionary television series on its foundations. From there it was a short hop to a sudden insight that Hong Kong gangster films created an intriguing mirror image of the American gangster metaphor. And then there was Dying to Belong: Gangster Movies in Hollywood and Hong Kong. With Dying to Belong, a third indispensable editor made her entrance in my life, the incomparable Jayne Fargnoli, my steadfast, adventurous publishing mentor/friend. David Chase and I are still talking, as well.

I had been a devoted teacher before lightning struck in the form of Tania Modleski's book.

As soon as I had my Ph. D. degree in hand, I began a teaching career, while I wrote during the time I stole from sleeping and squirreled away by refusing social obligations. Classrooms were almost always places teeming with life, hope, and achievement for me and my students. Some who have deeply influenced my work still shimmer brightly in memory–while a few continue to be a part of my life. But if I am in many ways a born teacher, it's writing and intellectual sleuthing–along with my husband, children, and friends–that form the core of my being. I ditched my tenured position as a professor in 2004 to write full-time. But I haven't ditched my interest in how students learn on the university level in the United States. I am currently writing World on Film, a textbook with a revolutionary approach to teaching international film to English-speaking students, under the aegis of Wiley-Blackwell, with the editorial support and encouragement of Jayne Fargnoli. My new freedom also allowed me to accept an invitation to be an Associate Editor at Cineaste.

The Privilege And Responsibility Of Reconsideration

With my new freedom came the need not only to move forward, but also the necessity for reconsideration.

Time depleted my feeling of satisfaction with my exploration of David Lynch's cinema in The Passion of David Lynch. 1997, as my book about Lynch was hitting the stores, was the watershed year of my doubts.

The catalyst was the release in that year of Lost Highway. Although I had tried in my last chapter of The Passion of David Lynch to fit Lost Highway into its quasi-Jungian theoretical framework, I could not escape the feeling that I had achieved no illumination of protagonist Fred Madison's (Bill Pullman) mutation into a complete stranger he had never met before, Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). What did this shocking mutability of matter have to do with the unified spirit that binds us all which I had extrapolated on in my book? Nothing. But I was also completely unconvinced by the approach being taken by other critics, who were spilling much ink trying to shoehorn Lost Highway into a structure of dream versus reality. As I saw it, presuming a dream/reality landscape as the explanation of Madison's metamorphosis into Dayton threatened to both trivialize Lynch and ignore the disorienting experience of watching Lost Highway. When you come down to it, that explanation of Fred's metamorphosis is much too reassuring. It does nothing but lead us away from seeking the secret of the discombobulation wrought in us by the physical havoc in Lynch's film.

By the time I saw Inland Empire (2006), even though I hadn't yet arrived at an explanation, I did have a direction. I had reviewed my early conversations with Lynch and realized that although I had dutifully focused on what he had said to me about the universal link among all human beings, from which I had extrapolated Jung as a useful point of reference, I had ignored everything he said to me about physics. Quantum mechanics, in fact. Do we routinely screen out what is not familiar? Or was I particularly intellectually lazy? Unwilling to make the effort to push myself beyond my limits to engage physics? Regardless, just as I knew in 1986 that Blue Velvet, the first Lynch film I had ever seen, was calling me to open up a new door; in 2006, I knew that my questions about Lost Highway and the films that followed were calling me to investigate a possible Lynch/quantum mechanics link.

Where to begin? Friends directed me to a New Age DVD called What The Bleep?: Down the Rabbit Hole, which considered the implications for our lives of the sciences. Or the implications according to a small group of enthusiasts. One physicist I knew spoke of What the Bleep? scornfully, and told me that one of the physicists interviewed had been misled as to what the DVD was about and had tried to sue the pertinent parties for deception. He wouldn't reveal the pertinent name.

The game was afoot! I followed a trail of clues to Columbia University and found Professor David Z. Albert, Frederick E. Woodbridge Professor of Philosophy and Director of the M. A. Program in the Philosophical Foundations of Physics. He took time out to teach me physics, and pick apart the problems posed by popularizers like those who had made What the Bleep? Since he loves the work of David Lynch, he was happy to talk with me about physics and Lynch.

On March 18, 2010, I told an astonished David Lynch about my study of physics, and an amazing three hour interview ensued, in which Lynch was so unguarded and forthcoming about my new ideas that he later insisted that I not print the transcript of our talk. Of course, he did not and would not ask me not to consider what was said as I wrote my new book, David Lynch Swerves: Uncertainty From Lost Highway to Inland Empire. And how could I not?As it has turned out, my first book, The Passion of David Lynch was a way station on my path, not my destination. As far as it went, it has been helpful to me and to my readers for engaging with Lynch as filmmaker. But when it would no longer serve...... The late and much missed Bob Sklar, told me it was dangerous to reconsider my earlier work in print in such a dramatic fashion. He feared it would raise alarm bells in the academic marketplace. And indeed I can imagine that some might think that if my first conclusion was not completely correct, I was likely to be unreliable in my reconsideration. But that kind of rigidity, as I see it, defeats the academic dedication to the life of the mind. My dear friend and editor Jim Burr, of the University of Texas Press backed me all the way. Although I truly am grateful for Bob's concern, here I stand. I can do no other.

International Negotiations

While I was undergoing my shock of recognition about Lynch, I took a trip around the world with Jayne Fargnoli, at Wiley-Blackwell. I was delighted to be working with her again. (I have been extremely blessed with support from the best and brightest in the publishing community.) That is to say, that with her support and counsel I designed World on Film, a textbook to introduce lower division college students to international film. My specific goal was to make available to college faculty a sorely needed address to bright but parochial students. My teaching experience had shown me that there were already plenty of usable textbooks for teaching the complexities of the best of American cinema, but I could find no books that would lend themselves to dealing with student subtitle phobia and student resistance to the much slower narrative pacing of so many international classics. How to open the door to Jean Renoir's surgical autopsy on the body of 1930s French class structure in Rules of the Game? Or to the fascinating but unfamiliar (to American students) sex god of poetic realism Jean Gabin? Or even the high action cinema of Akira Kurosawa and Wong Kar-wai? I longed to open doors for unprepared students to the masterful battlefield choreography of Ran and enable them to enjoy it while inhaling the translated dialogue at the bottom of the screen. I hoped to help them take in Kurasawa's narrative themes, by making familiar to them the unfamiliar values that ignited the flames of war in medieval Japan. I planned to help them make the effort to suss out the meaning of the odd translations of Wong Kar-wai's Hong Kong conversations set within a context of speeding images and incomprehensible situations. There were too many students who never guessed that there were enormous pleasures from which they were blocked.

But I did not long to write a textbook. Textbooks are fabled throughout the academy as gruntwork. Let's see, I thought, weighing the pros and cons: drudgery, necessity, drudgery, necessity. Necessity turned out to be the mother of excitement. Working on World on Film was as much an adventure as working with Lynch's films, albeit an adventure of a different kind. I was not headed where no one had ever gone before, but every decision I had to make brought new insight. Which film cultures? (A balancing act.) Which films? (Oh, no, I've got to talk about that one. And that one. And.....that makes too many.) Post World War II globalization? (When does national culture lose traction?) What's available? (Without buying a two thousand dollar return air fare ticket.) What's not? (Or will it be in a couple of months?) What historical and cultural fallacies have been perpetuated by cut and paste textbook composition? (That is, textbooks that merely assemble incorrect information from previous textbooks and regroup it.) How shall I structure World on Film to accommodate the best possible pedagogical approach?

Part of the fun was excavating deeper and deeper into European film cultures I already knew well. (And spending time with Jean Gabin and Marcello Mastroianni.) Part of the fun was stunning my Indian friends, who had little regard for any Indian filmmaker but Satyajit Ray. They never dreamed of the depth and breadth of their own cinematic history. (Or how interesting Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan's contribution to Indian cinema really is.) Part of the fun was renewing an old acquaintance with Japan whose cinema is so appallingly underrepresented in libraries and video catalogues, and forging new bonds with China, which is currently permitting independent filmmakers like Jia Zhangke to produce independent film, and submit it to European and American film festivals. (And interviewing Jia at the New York Film Festival.) NOTE: If these names are unfamiliar to you, you might consider reading World on Film. Part of the fun was discovering that Netflix, the much maligned 'red envelope gang,' has a better catalogue of old Indian and Japanese films than most university libraries. However, it was discouraging to find the paucity of women filmmakers available, and gut wrenching to negotiate between my interest in exposing my readers to the filmmakers who had most crucially influenced national traditions and cinema in the global village on the one hand, and my desire to expose readers to the contributions made by women. There were no instances in which both categories completely overlapped.

But the greatest fun I had was developing my image-based pedagogy. For a long time, I had been concerned with the poor use of film frames in too many film studies textbooks. The chapters were all logocentric. Images dangled off the expository paragraphs like obligatory decoration. Since logocentrism is the crucial problem with the way our students look at movies, and since this problem is compounded in the study of international film because in films made outside America there tends to be a parity between film and image, not a subordination of picture to prose, the very composition of most film textbooks seemed to be sending the wrong message. Trying to anchor my chapters in images as the impetus to reading the prose showed me why others had done it the other way. It's a challenge. If you read World on Film, you will be the judge of whether my 'What are you looking at?' feature that opens every chapter succeeds in changing the game.

Televisuality And Its Discontents: More Reconsideration

A long standing pre-occupation of mine is television, and television is growing more and more pre-occupying. The initial problem for students studying international film can be summed up as the hesitation before difference. The problem of studying television is the opposite. It is too familiar. Too ordinary. Its crumbs litter our living rooms, bedrooms, dens, game rooms, and sometimes kitchens and dining rooms. But I persist in thinking that the work I began two decades ago on the influence on narrative of the discontinuities built into the seriality of television with No End To Her: Soap Opera and the Female Subject (1992) is crucial to our understanding of the stories cultures tell themselves. I continue to reconsider that insight.

In No End To Her, I performed a service to serious students of television by tracing in the virtually endless narrative of soap opera a powerful counterforce against the misrepresentation of women, and also minorities, that is facilitated by traditional closed story form. At the time, I insisted that because the history of soap opera up until the writing of my book had proven that the gaps and endlessness built into the soap opera form had always privileged women an interrogated the male power figures who oppressed them, that such a value system was inevitable in soap opera.

As it turns out, the form can be perverted to privilege what is typically understood as conventional male entitlement and aggression. In the 1990's a slow turn began in which thug-like male characters became the primary figures on American soap operas, both in terms of the value the soaps placed on them (to the detriment of the female characters who had formerly been the major protagonists) and in terms of their importance to the stories being told on daytime. I was over-optimistic in my thinking that the form could not be misused against its own tendency to subvert a domination/submission definition of human relationships. After my time writing for the soaps, how could I have been so foolish? To paraphrase Fox Mulder, of the X-Files, "I wanted to believe."

However, in this case, time has proven me correct in my original beliefs. The tendency of soap opera IS toward the validation of feminine values not generally privileged in American culture. What I had not foreseen is the obliviousness of misinformed network management. In the 1990s, the insistence of the networks that writers skew their narratives away from the old narrative that had been based on the flow of emotion and toward the much more prevalent emphasis in our culture on narratives of power has lead to the destruction of a more than half of the soap operas that were on the air when I published No End To Her. At this writing, General Hospital, the only soap opera still being shown on ABC-TV out of a field of six that were on the daytime roster in 1992, is scrambling to cleanse itself of its gangster "heroes" and return to the previous, successful model of soap opera writing. I wish them luck, but am not currently optimistic.

In 1992, I had also simplified things too much by making the case that it was only the soap serial, which never reaches traditional closure unless it is cancelled, that would be able to tell liberatory pop culture stories. I now know that it is worthwhile to explore evening serial dramas and comedies to make manifest their use of the discontinuities and gaps of the serial form to alter the effect of closure on storytelling. Certainly, at the end of The Sopranos, creator David Chase demonstrated what could be done to the traditional gangster story by emphasizing the shock of the termination of the electronic images out of which his series had been made. Battlestar Galactica is equally interesting to study, but much more painful, since it collapsed from an experimental, three year subversive narrative experience into a conventional story as it began to reach closure in the fourth season. The Wire, Boardwalk Empire, and the latest subject of my interest, British comedy series Doc Martin, have piqued my curiosity to the bursting point. I went looking for Jim Burr again. I now have a contract for a book about "television beyond formula," the title of which is yet to be determined. Full steam ahead!

Televisuality And Its Discontents: More Reconsideration

As I work on this new book, I am finding that pinning down what we mean by formula is more difficult than might be imagined. It seemed very clear until I began to examine actual shows. Twin Peaks, The Sopranos, and The Wire are clearly beyond formula. But the history of television is not black and white. There are many shades of grey. Don't we go beyond formula television if a writer creates unorthodox characters even if they are shoehorned into a familiar plot structure? I can say, from experience, that television execs used to hear Gabriel's horn blow if we wrote even a line of dialogue that challenged truisms and clichés. What if a standard procedural includes many such lines, as does Castle, or a bi-sexual character, who isn't defined by her sexuality but rather presented to us as one of the cherished cast, as are the heterosexual characters in the series, for example, Angela in Bones? Is Breaking Bad, which is constructed according to the well worn patterns of crime melodrama, but features an intensely immoral, unethical protagonist—called an anti-hero in the popular press--formulaic, or beyond formula? And what is an anti-hero, anyway? Drama centered on guys who have done mighty wrongs have been around since Oedipus, and probably before that in unrecorded history. Doesn't the answer to this question depend on who has defined what is right and what is wrong, and whether the protagonist lives in a just or an unjust society; in a fathomable or an unfathomable universe?

My best bet now, as I do the spade work, seems to be to talk to the creators of what is being spoken about as if it is post-formulaic television. When people working in the industry are willing to speak to me, I find it keeps me honest and free from theoretical excess. In addition to my twenty-four years of interviews with David Lynch, I have now had eight years of revealing discussions (sizzling with wit, anger, and introspective examination of creative goals and artistic frustrations) with David Chase about what he was up to in The Sopranos and his thoughts about the entertainment media in America. Chase has also put me in contact with people that were crucial to the existence and continuing success of the series, including Richard Plepler, then the Executive Vice President of HBO, now the CEO; Brad Grey, then Chase's manager, now the CEO of Paramount Studios; Michael Imperioli, who played Christopher Multisanti on The Sopranos; Steven Van Zandt, who played Silvio Dante on The Sopranos, and was the music director on Chase's film Not Fade Away; and Allan Coulter and Tim Van Patten, two directors on The Sopranos. Chase has also helped me to interview Eigil Bryld, the cinematographer for Not Fade Away; Mark Johnson and Sidney Wolinsky, the Executive Producer and Editor, respectively, for Not Fade Away, and two of the stars of the film, John Magaro and Bella Heathcote. In my conversations with all these members of the creative community, I have witnessed a great deal of yearning for opportunities to express important things about human existence, and an intense exuberance that grew from the opportunities that David Chase gave them to do so. Stay tuned for more news about my research for my book about television with primary sources.

Goodbye/Hello

In October, 2012, I resigned my position as Associate Editor for Cineaste. I'd had a good time there, but was pressed for time and a new adventure called. For one thing, I had the great good luck to work as an Associate Producer for Chaotic Sequence Productions, Inc., run by producer,/writer/director Arthur Vincie. Found in Time is an ambitious movie, but Arthur's efforts have been rewarded with six first place prizes. I hope I will work with him again.

Up To My Eyebrows In Television

Beginning my "pre-production phase" for my book on television beyond formula, as usual, I find myself swimming against the tide. A great majority of critics, both journalists and academics, and I am excluding from my consideration "recappers" or patent shills for the networks, are focused on the problematic influence on television of network and cable hierarchies geared to lowest common denominator, massive audiences, and the commercial thrust of an industry in which there are at least as much energy and money invested in spot sales commercials as there are in the shows themselves; this does not even touch upon the corruption of the network and cable news programs that routinely suppress and spin events. But my attention is drawn to the amazing variety of the ways the creative community of television has defied and complicated formula. It is the sparks of life, real passion, and truth that I see emanating from the tube that compel my critical and scholarly attention. I have written about the mass media long enough to know that eventually the unbalanced importance of profits, the perverse pandering to the worst of audience responses, and the budgetary advantages of sticking to formulas eventually erode and contaminate almost every creation worthy of the name. But, and I write this with painful awareness that my choice of image is somewhat cliched, the fact that Camelot fell, the blistering reality that it was never what it set out to be and was at its best in its mythology of itself, does not invalidate the goals, the yearnings, the passions, the achievement that the ideal of Camelot undyingly represents.

It is to that ideal, for better or for worse, that I have directed and continue to direct my energies as a media scholar and critic. It is this that draws me to David Chase and David Lynch, in alphabetical order, two artists who miraculously, indomitably continue to say, to insist, as artists have through the millennia, "Only let me do the best I can do." But even, as was mostly the case with respect to daytime soap operas, if truth and beauty strike the media inadvertently, there is value and it must be noted and celebrated, just in case celebration might lead to intentional artistry. I salute, welcome, and appreciate expose criticism and scholarship, but I continue to ask, "Is that all there is?" What are the consequences of omitting from the serious cultural dialogue about the media acknowledgement of high achievement? I contend this is a chilling trend.

I have been naïve at times; at times, I have been mistaken; but I have not yet regretted the light I have insisted on shining on beauty, truth, or true creative love in commercial film and television, no matter how brief its life. But what has been does not strictly dictate what will be. If that makes you curious, stay with me for the ride.

Knee Deep In Hong Kong

In April of 2012, I signed a contract with Wiley-Blackwell, working again with Jayne Fargnoli, to edit the Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Wong Kar-wai. What a treat! This is a project very close to my heart. Wong Kar-wai is one of the greatest filmmakers in the world, and arguably the greatest living Asian filmmaker, and yet there is comparatively little written about his films. I have had the honor of assembling a literally world class company of 24 critics and scholars who will right this wrong. They hail from Australia, France, Hong Kong, Kuwait, Singapore, and the United States. The list includes Ackbar Abbas, Raymond Bellour, Giorgio Biancorosso, Kingsley Bolton, Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, Yomi Braister, Shohini Chaudhuri, Michel Chion, David Desser, Karen Fang, Matt Fung, Mike Ingham, Joseph Kickasola, Vivian Lee, Helen Hok-sze Leung, Gina Marchetti, Joseph McElhaney, Kenneth Provencher, Angelo Restivo, Berenice Reynaud, Carlos Rojas, Stephen Teo, Yiman Wang, Wai-Ping Yau, Esther Yau, and Audrey Yue.

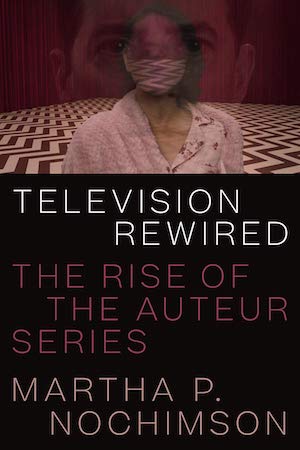

Television Rewired: The Rise Of The Auteur Series

Even before A Companion to Wong Kar-wai was published by Wiley in 2016, a new book began to take shape in my imagination. At the same time that Wong's cinema and the gloriously varied and diverse ideas of the critics I had assembled for the Companion continued to delight and occupy me as an editor, my own television viewing for pleasure had begun to fascinate me in a deeper way. I was increasingly riveted by the changes that started to take place on television in 1990, when David Lynch's Twin Peaks first went on air. I knew of several books about a new so-called golden and even platinum age of television, but I found them superficial, indiscriminate, and lacking in focus on precisely what had changed. Should The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Deadwood, Lost, and Battlestar Galactica really be considered in the same category as Twin Peaks, The Sopranos, The Wire, and Mad Men? What about Breaking Bad? Girls? Nurse Jackie? Enlightened? How to Get Away With Murder? All of these shows represent some kind of change from pre-1990 TV, but did they, I wondered, constitute the same level of evolution? And how did they relate to television history? What did The Sopranos, The Wire , and Breaking Bad have to do with the older crime shows like Columbo? Did the introduction of obscene language and dark situations and protagonists constitute a crucial break from the past? What was the relationship between the old sitcoms like The Mary Tyler Moore Show and new shows like Girls, Nurse Jackie, and Enlightened? Were nudity and flawed leading characters really the signs of a golden age? Was The X-Files different in kind or only in degree from Kolchak, the Night Stalker, the inspiration for the new show that chronicled Scully and Mulder? Ditto Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009) and the old series of the same name from the late 1970's?

As with all my books, urgent questions launched me into exploration before I really had any clarity about what I was looking for. As is my usual process, I stood back and let curiosity take me where it would. It took me back to talking with David Lynch, David Chase, and Matt Weiner. I went a-knocking on a couple of new doors too, and found Brad Anderson, Uta Briesewitz, and Nina Kostroff Noble, who led the way to David Simon and Eric Overmyer. I couldn't get interviews with Lena Dunham and Laura Dern, with whom I very much wanted to speak, a big disappointment. But the conversations I did have gave me my focus for my new book. I soon saw I was looking at a new landscape on which there was a big distinction between artists working in television and formulaic craftspeople, whom some cruelly call hacks, but who may be master craftspersons although not artists. The more I watched; the more I thought; the more I spoke with a very specific group working in series television, the clearer it became to me that beginning in 1990 there had been a clean break between the new auteur television and all the old series. It was also clear that auteur television had very little in common with new formula TV. We were witnessing the beginning and expansion of television as a medium in which art could be created by auteurs but was flooded with formula shows which imitated the superficial characteristics of the auteur series'. I decided to call it formula 2.0; most of it was little more than routine narrative with a few new bells and whistles. Some of it was highly skilled and inventive, but none of the 2.0 series' was--as are the work of Lynch, Chase, Simon, Overmyer, and Lena Dunham-- a new form of literature, a successor to Joyce, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Kafka, Hemingway, and perhaps Virginia Woolf.

This insight blossomed into Television Rewired: The Rise of the Auteur Series by fomenting a struggle to articulate the distinctions I intuited between auteur and formula entertainment. What was it that the television auteurs had in common with the greats of western literature that was not to be found in even the best of formula series' 2.0? I arrived at some answers to that question which cannot be summed up in a sound bite, but rather needed many chapters to explore. No one will be surprised to learn that the answers had to do with personal vision, and kinship with the great modern ideas and practices being developed by cutting edge science, philosophy, psychology, and fine art. No one will be surprised to learn that where the auteurs challenged audiences, formulaic series' developers comforted them. False comfort? I think so. Even after five years of research and writing, my interest is still quickened by new thoughts about auteur television series' and their unusual relationship to the media.

Television Rewired will be published in July 2019. The work I did for it has generated many insights but also many questions I did not have before. In the last year of my work about auteur television, my old friend and gadfly, curiosity, began to tickle those subterranean recesses from which all my best ideas come to me unbidden. What, I ask myself, do I actually know about formula 2.0? While I was concentrating on auteur television, I didn't have time to ask a question that is now tugging at my imagination. I've written a lot about what art means in the form of a television series, and that has made me more curious about the inner workings of ordinary formulaic entertainment? I'd get a couple of books on the subject if I could, but you see, although there have been many weighty speculations of a partial nature about the culture industry, for example about sexism and racism, there are no books that are seriously speculative about the incredible lightness of being of diversions most people think of when they hear the word "entertainment." That's right, and there's a little voice that keeps saying that there should be. Entertainment—frivolous, intense, familiar, repetitive, temporary and disposable--what is it and how does it work? How can it be distinguished from other forms of easy watching popular discourse? Or does everything that isn't art come under that rubric? Hey there, voice; are you talking to me? Are you talking to ME?

Watch this space.